Gbonka, our beloved Babalawo, is failing woefully to conclude the final rites of Adunni’s earthing, so she continues the spate of destruction from last week. It doesn’t help that she’s growing ever more angry and powerful. Gbonka has just this one chance to wrap things up right, or else Adunni won’t stay. She’ll go the way of every Abiku and make herself die. Meanwhile, Adunni meets Labake, her birth mother, face to face. It is horrifying but beautiful encounter.

As I slipped through the dining room wall, I shed all restraint. I wallowed in centuries of anger and frustration. I exulted in my power, in my strength. I was on a high.

I threw lightning like confetti. Holes were punched through the roof, the floor, the walls of the house. The destruction must be systematic. It must be complete.

Haven’t I become all I was created to be? An automaton created to do the will of ‘the powers that be’, a slave! That’s all I’ve always been, a bloody slave!

“Yes massa! No massa! Three fucking bags full massa!” I said as I let loose another volley of lightning and watched with pleasure as it bounced around the kitchen, turning everything in its path into ashes.

Let the universe mete out any punishment she likes. I’m done with being good!

I laughed when I threw another round of bolts and nothing happened. So I can no longer channel Sango. He’s taken his powers from me. Well I’ll channel me!

Red, the color of fear filled the atmosphere. The color sent out by my mortal family, my power source… my prey.

I became even stronger as I absorbed their fears.

Pah! They are not even afraid for themselves. They are all thinking of the baby. I snickered. The thing is I cannot even kill them. I can make life happen, but do not hold the power of Death. Oh well, the least I can do is make their fucking lives miserable!

I tore out the water pipes embedded within the walls, the mains pumped out its contents, flooding the house.

Restraint. Cunning.

Pop! Pop! Pop! Went the bulbs.

Control. Wisdom.

Crash! Went the ceiling fans.

What the fuck? Why the fuck should I allow those things to master me? Why the fuck should I restrain myself? Isn’t that what I’ve done ever since I gained consciousness? Haven’t I been a good little Abiku? Mother Earth’s favorite simply because I’ve always followed the rules, toed the lines, kept my head no matter what happened.

The house shook in rhythm with my anger. I pulled out the television and threw it through a wall.

Isn’t this the reward for my being good? A bloody complicated birth!

I die to live! Die to live! Lost, loved, lost, lost, lost!

Shuttling between mortality and immortality like a bloody zombie!

“And for what fucking reason? Oops! My bad, I forget, We-Do-Not-Question-The-Universe!”

I became one with the wall and poured into father’s bedroom.

The first thing I smashed was his daft iPad, then his bloody laptop. I paused at the stupid bed where my mortal body had been conceived, missionary style, (bloody unimaginative humans!) and flung the ugly King Sized bed through the window. I shivered in satisfaction as the glass windows and most of the wall blew out.

I threw a dense fog around the compound, throwing that tiny bit of earth into semi-darkness.

Muffled whispers came my way, and I threw a chair in that direction. Silence reigned once again.

I want them to hear clearly, the music of destruction.

I tore out the bathtub in father’s bathroom, suspended it in air. It gathered momentum as it fell and tore through the floor. The noise it made…music to my ears.

I’m in no hurry, so I watched as thick dust rose up from the ground, twinkling like a million stars while my created the backdrop it needed to shine.

Isn’t that what we are? Fucking cosmic dust!

“Adunni, you don’t need to do this. Please calm down, let’s talk.” Gbonka’s voice rang out.

“Who the fuck are you to tell me what I can or cannot do?” I bellowed at him. “You puny, filthy, human being! I will show you the full extent of my powers! How old are you, Gbonka? Tell me you slimy little thing. A mere babe! I warned you Gbonka! I fucking warned you!”

I still couldn’t enter the sitting room. Gbonka had done his homework, but I worked through the tiles on the outer walls and flung them in all directions.

I devastated the laundry room, mother’s room, the guest bedrooms, the study. I tore doors off their hinges, smashed sinks, toilets, tanks. I destroyed, destroyed, destroyed every little thing in my path!

I spotted Ruth and Chinonye heading for the front door. They had Labake and Jesutitofunmi wedged in-between them.

I sent a gust of wind at them, and they all fell down like a house built with spittle. I shoved mother into a room on my left and sealed the entrance.

Chinonye and Ruth tried to run in after her, but I pulled up the earth into a small hill and they slid off like the little children that they are.

Chinonye turned on me and started yelling incantations.

“Oh shut up!” I said as I sealed her upper lip to the lower one.

She looked totally ridiculous as she felt for her mouth desperately, her throat working up and down. I couldn’t suppress my laughter. She went sailing through the front entrance as the force of my power hit her.

Instead of running for her life, like any sane human being would have, my ‘brave’ grandmother, Ruth, kept trying to get through the sealed off doorway. I sighed in exasperation as I tore off her gown, snapped off the straps of her bra and pulled down her panties before throwing her after Chinonye.

Let her be naked. Let the sun beat her. Let the rain soak her to her bones!

I summoned the elements and in my fury they had no choice but to answer.

It rained and thundered. The sun shone fiercely all through this. I clapped in glee as the two women made for the tent where my naming ceremony had been held earlier. I sent a couple of thunderclaps and lightning their way to ensure they don’t come out from underneath the tent anytime soon.

I skipped through the house singing my favorite Yoruba song.

“Osupa olomi roro

Bo ba d’amodun o wa gbekuru je

Ole! Aboju wonpa!”

Hey moon, shinning silkily in the night skies

We will offer you steamed bean paste during festivities

Greedy thief! With your roving eyes!

I should have done this before! Now I know why Abikus are so mischievous. This is so much fun! I ran around the house singing my song. It rang out beautifully, but all human beings around will hear it like an eerie, otherworldly sound.

It is gorgeous, this destruction. Chaos is beautiful.

I listened for Gbonka’s heartbeat. He was gone, the sneaky bastard!

I went after father but found Titus cowering behind a huge tank in the backyard. I idly picked him up, held him close to me and fed on his fears, his hatred. By the time I allowed him to slide out of my arms he slumped on the ground in a near faint, emptied.

It is amazing, this power flowing through me. It is an aphrodisiac. I want to mate with the universe herself.

As I resumed my search for father, I was suddenly surrounded by spirit beings on their knees.

Witches.

Chinonye’s coven.

“We have come to seek a boon of you…” the leader of the coven started.

I did not pause as I lifted them up, mashed them together and sent them back to where they came from.

I hummed as I entered the room where I’d sealed Labake and showed myself to her in my full glory. I did it gradually, legs first, then my torso. By the time I showed her my face she was screaming at the top of her lungs.

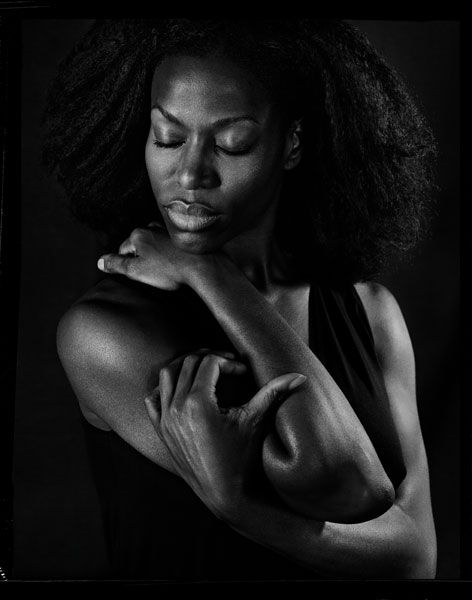

I laughed at what she must have seen, a towering darkness in shape of a woman. Eyes ablaze, thick bushy hair standing on ends, fire spurting out of her fingers, mouth, nose, ears. I am the embodiment of her worst nightmares.

“Hand over that baby to me!” I thundered at her. I thinned out and then pulled every atom of my body together. I became fire in shape of a woman.

You show. You don’t tell.

“Hand that baby to me!” I growled as I sent spurts of fire at her.

She curved her body around that of the baby. “No please, no. I can’t.” She cowered in a corner. When she turned her face to me it was full of determination.

“I won’t.” She said. “Kill me first, take me to hell with you, but you won’t take this child from me.”

“You’re not holding your child Labake. You’re holding me! And I want her back, she’s mine!” I screamed at her.

“Jesutitofunmi, I love you. I don’t care if you’re from the pits of hell. I don’t care if you are demanding. I love you! I love everything you are. You are the child of my womb.” She whispered to the child in her arms softly.

“I am nothing of the sort! I am Abiku. I am of the spirits, the elements. I created that child within your arms, and I want her back. Give her to me!” Why the fuck is she talking about love?

“Even if you created the child within my arms, you did not create yourself,” she turned her face towards me, “somebody or something must have created you. And I lodged you and this baby in my womb for nine months. Does that count for nothing?” She took a step towards me, her eyes earnest, “I gave you my heartbeat, shared my blood with you, allowed you to flourish, nourished my body so you can be nourished. I pushed you through my vagina! Bathed you in my blood! You are mine. We have a blood pact. I don’t care who you are. You are mine!” She said, her eyes blazed with a fire all of its own. “Kill me now, and you can have this child, otherwise, I am not handing her over to you.” She finished calmly.

I looked at her with fresh eyes. She’s a lioness!

“You have not been told how worthless you are all your life. You’ve not failed at everything you’ve ever done.” She forged on, her voice was low but strong. It filled the room.

“From childhood my own worthlessness has been shown to me. I can do nothing right. I have no special talents. I have never been brilliant academically. I can’t sing, dance or draw. When my brothers and sisters were graduating from different universities, I was still failing the University Matriculation Examinations and GCE spectacularly. Even when I turned my hands to business I failed. Everything I laid my hands on turned to dust.” She said with self acceptance. I tested her words for traces of self pity but found none.

“I am not even particularly beautiful. When my mates were experimenting with drugs, sex and boys, I was in church night and day, praying for a turnaround in my story. The only thing I’ve ever done successfully was to marry your father, not because he loved me, but because of a prophecy given by one of the pastors in the church that we were soul mates. Your father never loved me. What’s there to love about me? By the time your father married me, I was already on the shelf, a twenty six years old virgin of no particular talent. He married me for the church and his father, not for himself.” She pulled a chair upright and sat on it.

Her story was fascinating, I settled down beside her. For the moment, I pushed aside my rage and allowed her words to wash over me.

This is one thing you never get from the dossiers you get on human beings. You have access to all their actions but not the inner workings. The dossiers never told you why. It tells you what, when and how, but never why.

“I have paid for that one thing. Every single day of my marriage to your father has been a punishment. To worsen matters I couldn’t even give him a living child. So he cheats on me with different women, hoping to prove that our childlessness is my fault, not his.” She laughed bitterly, “but his various mistresses don’t even conceive, talk less of birthing a child.”

“Do you love your husband?” I asked her.

“Do I love myself? Have I been loved? How can I give what I don’t have? It’s either this marriage or become one of those dried out women in church, poor and lonely. At least, with your father, I’m financially secure.” She smiled wryly.

“But I’ve loved every single child I’ve birthed and lost. I’ve loved them with every fibre of my being. They were puny and sickly from birth, but I loved them. I loved them because for the first time in my life I felt as if I was doing something right.”

She sighed and closed her eyes. She opened them a minute later and looked at me, all her fears gone. She looked at me with love.

“But you, you’re perfect, and I love you. I want you as my daughter. I don’t care what you are. I’ve always felt your presence even through my denials. You’re my daughter Oluwafikunayomi, Asake, Omosalewa, Omolewa.”

She caressed the baby’s cheek, looked at me and stretched out her arm as if she wanted to touch me too, but she withdrew it and sighed, “For the first time in my miserable life I have something I can call my own. Please stay, child of my heart. Stay for as long as you want. I will love you for every single day you’re with me.”

I felt uncomfortable, like something was unfurling inside me. Damn it!

I hid my face from her.

It is strange, this feeling, because for the first time since I’ve been created someone is accepting me wholly, in all my unholy difference.

I opened my mouth to say something, but shut it again.

I sensed there was no need for more words.

As I pondered on the unexpected turn of events I heard Gbonka’s voice again. He was chanting incantations.

“Adunni, su re tete bo si bi,

Baa ba p’oku ni popo

Alaiye ni n daun

Adunni

Sure tete bo si bi.”

It was Gbonka.

“Come speedily, Adunni. When we call the name of the dead in a crowded place, the living responds.”

I felt a tug, but instead of floating off towards Gbonka’s voice, I was yanked upwards.

Floating just a little above the house was Ebora, one of Mother Earth’s servants.

“Ile is waiting for us,” He said as he grabbed my hand.

***

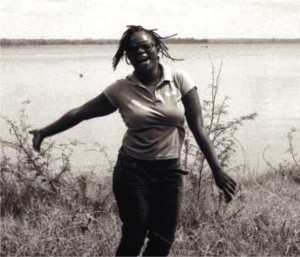

Born in Ibadan in the early 70′s, Ayodele Olofintuade spent her holidays with her grandfather who lived a stone’s throw from Olumo Rock. He nurtured her young mind by making her read Yoruba classics like Ireke Onibudo, Irinkerindo ninu Igbo Elegbeje, Ogboju Ode ninu Igbo Irumole to him. She read Mass Communication at the Institute of Management and Technology, Enugu.

Born in Ibadan in the early 70′s, Ayodele Olofintuade spent her holidays with her grandfather who lived a stone’s throw from Olumo Rock. He nurtured her young mind by making her read Yoruba classics like Ireke Onibudo, Irinkerindo ninu Igbo Elegbeje, Ogboju Ode ninu Igbo Irumole to him. She read Mass Communication at the Institute of Management and Technology, Enugu.

She is a writer, spoken words artiste, teacher and editor, who has been a graphic artist, sales girl, cybercafe attendant, dance instructor and information technology teacher. She has worked with children in one capacity or the other in the past 13 years. She presently runs a project called Laipo Reads, a community/mobile library that makes book available to children. Olofintuade was the first runner up in the NLNG Prize for Literature 2010.

The image was exclusively designed for this project by the insanely talented Laolu Senbanjo.

The story continues next WEDNESDAY.

To be the first to read the next episode:

You should follow Brittle Paper on Twitter HERE

You should like Brittle Paper on Facebook HERE