![]()

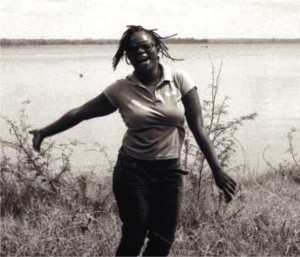

Adunni lets us in on the Abiku worldview. She dishes on what it’s like to be a spirit being and how the human world appears from their side of the world.

Plus, it’s a big day for her. Final earthing rites take place tonight. After midnight, she wont be able to die for a good many years. And if you know anything about Abikus, you know they hate not being able to die. Trust Adunni, who has serious anger issues, to work herself up into a storm.

EPISODE ONE EPISODE TWO

EPISODE THREE EPISODE FOUR

![adunni-abiku-afromysterics-brittlepaper-olofintuade-adunni]()

After Edward left, the house breathed more easily and the afternoon sunshine filled every room.

Gbonka fell asleep in the armchair he was occupying, exhausted from our fight with the Egberes and his adventure in the skies.

Father drifted into his room and started chatting with his various girlfriends on his ipad. I peeped into the screen just as a nubile girl of about 18 years sent in a picture of her sitting on a dildo.

Ruth went to fetch some food from the kitchen while mother lay down with me on her chest.

I merged with my body and reflected on the way things are, the way they will always be.

How, from the moment we gain consciousness, the powers that be told us how amazing we are, how superior we are to the human race.

“You live outside of time. You are beautiful and can garner enough power to make things happen in the cosmos and most importantly you’re free.”

“Observe,” ‘They’ tell us, “observe the way human beings are raised from childhood, how cleverly they manage to pass shackles from one generation to the next.”

And we do, we watch how imprisoned human beings, in turn, raise their young within the limits. We watch how brilliantly they manage to slide chains round their children’s necks. Human children are taught to bear the brunt of their parent’s joy, sadness or anger from birth.

Then, like products on an assembly line, they are forced into moulds, one size, of necessity, must fit all. They are not allowed to think differently. They are, in fact, punished for being different. A bird is not expected to swim with the whales.

As they grow older, click goes on the chains of education or a lack thereof, of class, money, marriage, children, religion, and people’s opinion… the list is endless.

I watch as they casually toss the word freewill around like it’s a basic right. Freewill, I snicker at the word. Freewill indeed! Freewill that can only be exercised within the limits of societal expectations. What freewill?

Come to think of it, is there true freedom for any being? Aren’t we all at the mercy of the universe?

Ask me why I’m an Abiku, ask me why I do what I do, ask me the point in all of this, the need for it … I have no answers.

But … we are free.

Then ‘They’ tell us, “observe human emotions, how messy and out of control those things can be.”

We do. We watch how emotions never change from one generation to another, love, envy, happiness, passion, need, greed, wickedness, in spite of all the advances they’ve made in the sciences and arts, human beings are yet to master their emotions. Impulsive actions still account for over 40 percent of the crimes they commit.

“You are immune to all these,” They say, “you’re above human passion.”

If this were true, how else do I describe that feeling of power when it flows through me? Power is a perpetual hard on. It is orgasmic.

How do I describe the ecstasy of the dances that we all struggle to participate in on moonlit nights, the orgies. What word fits the freedom of playing like little children, traipsing through the stars, dancing on the moon, playing hide and seek, coupling?

What other word can be used to describe what I feel each time I watch another set of parents weep over my dead body? That heady, tingly feeling you get while racking up power. The closest to that feeling human beings get is when they reach orgasm, that point your head implodes and you become invincible, that moment you become one with your partner, one with nature.

How about the reluctance that accompanies each death? That reluctance to let people who idolize you so much go, sadness at the thought that Time, that stealer of memories, will soon ravage the minds of people who have given you so much, people who have given you their laughter, love, their tears, their sadness, depression.

Am I passionless each time I come to a full cycle? Do I die to live … indifferently?

But then, we are not expected to question the universe.

We do not. Question the Universe.

I screamed my frustrations through my mortal body, expanded my lungs to their fullest capacity and wailed, causing mother to abandon her meal.

“If you keep this up she will grow into a proper little tyrant.” Ruth said idly as mother clutched me to her breasts, a child’s favorite toy.

“It’s still new to you. Wait until she starts waking you up every five minutes after midnight. Especially on days you’re bone tired and all you want is a good night’s sleep.” Chinonye added.

“You forget I’ve had children before. Both of you are acting as if this were my first child.” Labake said, but she neglected to add ‘…and it’s none of your business how I choose to raise MY daughter’ because she was not ‘that’ kind of woman. She might think it, but she would sooner burst into flames than utter such blasphemy.

Mother pulled her thick lips into a line so straight you could use it to rule paper. It struck me how unattractive mother really is. I don’t mean her physical features. Those are not so bad, with her slight overbite, thick lips, snub nose and wide spaced eyes, she can even be considered beautiful, especially with her fair skin, enhanced by the ‘Fair and White’ Anti-ageing cream she had taken to using soon after my birth.

But something beneath the surface is repelling. She’d restrained herself from expressing negative emotions for so long that all the poison had seeped out of the place within and created a negative aura around her.

“This one is going to stay. I can assure you that if you keep smothering her with affection you will not be able to cope with the monster for attention you are creating.” Ruth said.

“Don’t mind her Mama Gbenga. Her eyes go soon clear.” Chinonye slapped Ruth’s thigh familiarly and cackled.

“How are you sure she’ll live past her first birthday? I’m surprised Mummy GO is taking the word of an old idol worshipper so seriously.” Labake said.

“Ah!” Chinonye said, “Are you praying for your daughter’s death?”

“No! She will live. She will not die, in Jesus name.” Labake said fervently.

There was a pause. Ruth manipulated the silence such that Labake and her mother eventually directed their attention to her.

“Don’t ever talk about my father-in-law with that tone of voice ever again.” Ruth said, her eyes were chips of ice. She allowed her words to sink into Labake’s heart, then continued briskly, “but I understand your anxieties. You, my dear Labake, are suffering from a perpetual Christian problem, that of ‘having a form of godliness, but denying the power thereof’.”

“I’m sorry I talked about Grandfather like that. It will never happen again.” Labake said with an appropriately humbled tone practiced over the years, but she continued. “How can you be quoting the bible to support powers outside that of God?”

Ruth sighed in exasperation and her eyes took on a mean look, but Chinonye jumped into a conversation that was fast becoming a conflagration. She wondered how she managed to raise a daughter as obtuse as Labake.

“Abeg shut your stupid mouth. See her talking about things she nor understand. A child who does not recognize medicine and insists it is vegetable.” She sucked her teeth for emphasis.

“I’m sorry mother.” Labake apologized. Her default mode is the ever smiling, ever apologetic, submissive Christian woman, but I can see the darkness underneath that smiling exterior, a dark shade of green, putrid, a suppurating wound.

This woman will blow up someday. Her absolute focus on having a child to call her own, the need to leave the caucus of women who had to attend special prayers for ‘barren’ women helps her control the darkness inside. I know that once she’s got what she wants, she would let loose the monster within and Gbenga will pay for all the ill-treatment, both real and perceived, she’d received at his hands.

“We shall see, won’t we?” She muttered through stiff lips.

“Did you say something?” Ruth asked her.

“Oh nothing mother, was just playing with Jesutitofunmi.” She hummed a song to me as the older women resumed their meal.

I drifted out of my mortal body as soon as mother placed me back in the bassinet.

The house was quiet, having been emptied of all the hangers on and the insistently curious. Ruth must have cleared it out, for she’s the only one with enough steel in her spine to achieve such a feat. People from this part of the world are famous for their love for lingering around anywhere there’s drama, food and liquor in abundance.

With nothing else to do I went back into the sitting room where Gbonka was in a deep conversation with father. After a while, as if by some unspoken agreement, everybody else drifted into the sitting room.

Ruth Lamorin – paternal grandmother.

Gbenga Lamorin – father.

Labake Lamorin – mother.

Chinonye Lasisi – maternal grandmother.

Gbonka Lamorin – great-grandfather.

I ticked off the list of the dramatis personae in what was turning out to be one long ass day. The only person that was not related to me by blood in the room was Gbonka’s acolyte.

He was a blank slate. I zoomed inside of him and found nothing but thoughts of winning the lottery and becoming an overnight billionaire. I find such people repulsive. Nothing is as unattractive as a human being who lacks imagination. At least he knows his own name, Titus.

I know his type. They are the ones hurling the first stone, the ones with the matches and machetes whenever there’s a mob action.

I backed off from Titus before Ignorance, a spirit attached to his medulla oblongata, senses my presence. Those creatures are usually tiny, but his has grown fat, spreading its tentacles over his brain like cancer. Ignorance usually develops a symbiotic relationship with its host, feeding on all the kind thoughts a person has and giving in return hatred. Those things are vicious, with their pink eyes and sharp teeth.

“We can’t do anything till midnight. The earthing rites should have been carried out at noon.” Gbonka said after a while. “I suggest we should rest now so that we will have enough energy to do the needful at midnight.”

I followed father to his room and admired his muscular body as he stripped off his clothes. Father swims every morning before reporting for work, and it shows in his broad chest, well defined muscular arms, a trim waist and strong flanks. He entered the bathroom, turned the shower to full blast and closed his eyes as he lathered his body.

When he got to his penis he began caressing it hesitantly at first, then harder. The room was filled with images of the nubile young girl with tits the size of melons that had sent him her nudes earlier. I watched the rapid motion of his left hand as he masturbated to the rhythm of a Barry White song being piped into the bathroom.

Just before he exploded, the image of a man entering him from behind filled his mind and he muffled his shout against the smooth tiles on the bathroom wall and trembled.

About the same time a buzzing filled the room, an unearthly noise that was closely followed by thick plumes of red, yellow and blue smoke, the colors of magic.

I instantly abandoned father and his forbidden desires and followed the direction from which the smoke was coming. The closer I drew to the sitting room the thicker the smoke became. I entered and discovered the sitting room had been transformed into a shrine.

The rug that had been spread from one corner of the room to the other had been rolled back and most of the furniture had been moved out.

In each corner of the room were four tiny clay pots, Sango’s pots that do not need fire to boil even the hardest of stones to a mushy consistency. Clothes dyed in indigo were hung all around the room and the statues of Oya, the all-giving mother, and Osun, the abundant one, were placed on either sides of Obatala, the truth.

Gbonka was in the process of drawing my image on the floor with a stick of Camwood. I tried to move closer and inspect what he was doing but was stopped by a powerful blow to my midriff.

“Why are you doing this Gbonka?” I said, my eyes a narrow slit.

“I don’t want you poking around and messing things up for me.” He replied without looking up from what he was doing.

“I won’t do that! I’ve given my word!” I yelled at him.

“Your word means nothing! I am taking all precautions against you changing your mind.”

“I want to know exactly what you’re doing. I want to know the gods and spirits you’re summoning! I want full disclosure. I won’t be closed out! You promised that there are to be no secrets between us.”

“I promised no such thing, in fact we never discussed your earthing rites so I don’t understand why you’re getting all worked up.” Gbonka said.

His acolyte chose that moment to enter the sitting-room, the fool walked right through me and he didn’t even flinch. He was in a white loincloth and had white chalk markings on his body.

Gbonka straightened up and swept the boy a dirty look from his head to his toes.

“What is wrong with you? Why are you dressed like this?”

“I thought…” the boy started.

“Don’t think. You are not good at it. That’s why I do all the thinking around here. Kindly go and clean all that rubbish off your body and be back here in five minutes with your shirt and trousers.” Gbonka said.

I took that moment of distraction to throw a couch at Gbonka.

“These are the kinds of rubbish we get these days.” He said as he waved the airborne couch away like a gnat. “Finding people willing to follow the old ways has become so difficult. The boys and girls are no longer interested in the art. They want me to teach them within a year what I spent a lifetime acquiring.”

The couch landed with a thud right back where it had been earlier.

“In my days, there are always at least ten trainees working with each Babalawo. But to even get someone to stay long enough is becoming a struggle nowadays.” He continued marking the floor as if I hadn’t just tried to kill him with a chair.

A scream rose from my insides and came out as a high pitched note well beyond human hearing. All the dogs in the neighborhood started howling. I sent a barrage of objects at Gbonka, a stool, a giant cooking pot somebody had left in the passageway and two iron buckets.

As the objects broke through the barrier Gbonka had thrown around the sitting room, I launched myself after them but suffered another punch, this time to my chest, which sent me sprawling.

What manner of power is this? Who could have given him this strong talisman?

I know beyond a shadow of doubt that Asake does not have that kind of power. None of us did. The gods had gone and done it again! I turned into a whirlwind and swept through the passageway. Chairs, stools, wall fixtures, the books lined on shelves and the shelves were caught up and flung every which way. There was a cacophony of objects being smashed as I swept into the dinning room.

I stood still in the dead centre and stretched out my arms. I was a conductor and all the furniture in the room was mine to command.

I made the dining table dance a jig. The chairs bounced up and down, the rug rolled itself up and the wall tiles were yanked out one after the other. With infinite care, the pages of Gbenga’s favorite books were torn out.

The windows opened and shut by themselves and ever so often allowed the objects a free passage to the world outside as I flung them with grace.

Gbonka walked through the flying objects. The protection around him was thick. Every object I sent flying at him bounced off—knives, pots, pans, chairs, the dining table.

“Look, stop wasting my time and your energy. There is nothing you can do about this situation!” Gbonka said as he stood just outside my storm, not making any move to dodge the air-conditioning unit I just pulled out of the wall and launched at him.

I stopped throwing things and mutely summoned lightning. As I felt naked electricity flow into my body, I gave myself up to Sango. I am a vessel of anger.

“What’s going on granpa? I heard the sound of things being smashed.” Gbenga asked from the doorway. Craning their necks behind him were other members of the family.

Gbonka used a blast of air to push father and the others out of the way. I threw lightning their way. The white/blue flash burned the door into ashes and as Gbonka sealed the doorway with àfòse, the lightning bounced back into the room and burnt a giant hole in one of the walls.

He began circling me, chanting my names, the ones he knew.

I laughed gleefully, genuinely.

“So with all your powers, you still don’t know my real name!” I taunted him, “have the gods suddenly become forgetful? Or did you forget to ask for my name? Are you such a novice that you don’t know that there’s nothing you can do to me without it? Let me tell you something you’ll never earth me!” I sputtered with more laughter as I slipped through the wall closest to me.

Gbonka has forgotten that he who hides under a calabash can never carry his children along.

***

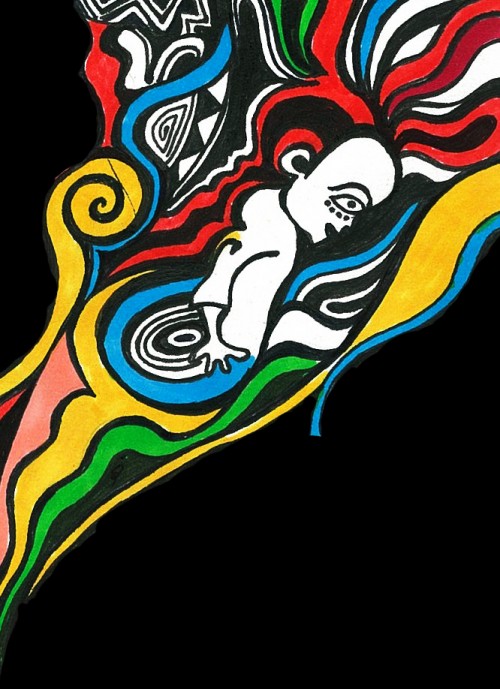

![Ayodele-olofintuade-abiku-portrait]() Born in Ibadan in the early 70′s, Ayodele Olofintuade spent her holidays with her grandfather who lived a stone’s throw from Olumo Rock. He nurtured her young mind by making her read Yoruba classics like Ireke Onibudo, Irinkerindo ninu Igbo Elegbeje, Ogboju Ode ninu Igbo Irumole to him. She read Mass Communication at the Institute of Management and Technology, Enugu.

Born in Ibadan in the early 70′s, Ayodele Olofintuade spent her holidays with her grandfather who lived a stone’s throw from Olumo Rock. He nurtured her young mind by making her read Yoruba classics like Ireke Onibudo, Irinkerindo ninu Igbo Elegbeje, Ogboju Ode ninu Igbo Irumole to him. She read Mass Communication at the Institute of Management and Technology, Enugu.

She is a writer, spoken words artiste, teacher and editor, who has been a graphic artist, sales girl, cybercafe attendant, dance instructor and information technology teacher. She has worked with children in one capacity or the other in the past 13 years. She presently runs a project called Laipo Reads, a community/mobile library that makes book available to children. Olofintuade was the first runner up in the NLNG Prize for Literature 2010.

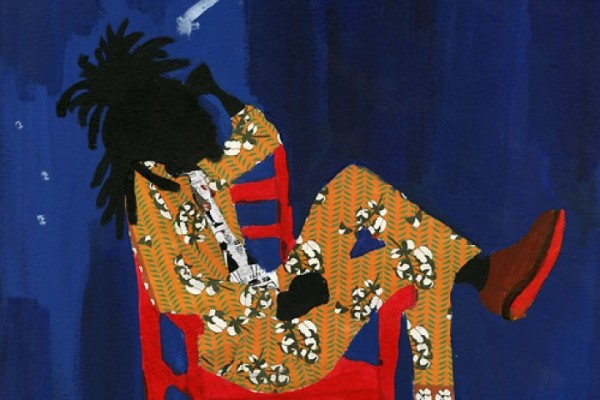

The image was exclusively designed for this project by the insanely talented Laolu Senbanjo.

The story continues next WEDNESDAY.

To be the first to read the next episode:

You should follow Brittle Paper on Twitter HERE

You should like Brittle Paper on Facebook HERE