![]()

What does a butterfly and a penis have to do with God, the universe, and the secrets of creation? Perhaps the Bible and quantum mechanics, Satan and Pythagoras, time and the tarantula aren’t such different things. Perhaps when brought in relation they hold the key to the power of poetry.

The Testament of Sand by Nigerian poet, Umar Sidi, explores these quirky and titillating ideas. In 290 lines of poetry that enchants the open-hearted reader, Sidi explores the thread that runs through the cosmos from man to God and back.

Testaments of Sand is that weird moment when prayer and invocation slips into an erotic love song. Braze yourself because the poem will take you through winding pathways of ideas about time, history, the body, and divinity.

Warning: DO NOT read this poem like a textbook, meaning don’t try to figure it out. Imagine a question that has lost its answer or a puzzle that has lost its key. If you trying to figure it out, the poem will close itself to you and you’ll leave it having gained nothing. If it’s a only word here, an image there, or a sound, a sentence that speaks to you, hold on to it.

I am so pleased to begin the year with Umar Sidi’s Testaments of Sand.

![SID EL HOUARI WAHRAN 1]()

Testaments of Sand (Genesis or Book of God)

*

Al- Arshad poet of sand

Al- Arshad poet of dust

Al -Arshad poet of the testaments

AL – AR – SHAD poet of mud

*

Al- ARSHAD poet of sand

poet of the ocean of sand

where sand particles are consumed

like fine grains of milk

Al- ARSHAD poet of dust

poet of the waterfalls of dust

poet of the expanding worlds which are swirling

over infinite space as floating quarks of dust

Al -ARSHAD poet of the testaments

the Tall tambourine of the family of drums

the accursed poet, the black sheep,

a tarantula, who testified against the tentacles of time

AL – A R S H A D poet of mud;

they said you were there when God moulded mud to make man in the image of Man

they said you were there when God breathed into Man the immortal Breath of God

they said it was you who scribbled the destiny of Man on the bare Soul of Life

they said it was you who implanted the Fall in the Scroll of Life, as metaphor for twist of fate

they said you are Eve, or the aromatic curves of Eve

Some said you are the vituperative fangs of the Serpent

Some said No! You are the bushy valley of life, the forbidden fruit tucked between the mighty thighs of Eve

they said it was You who created mythos to distract Man from deciphering the original face of God hidden behind palisades of clouds

they said it was You who carved out logos from the left ear of God

they said it was You who created the alphabet and encrypted it with metaphors

![SID EL HOUARI WAHRAN 2]()

and when God said let there be light, You were there, as the Form of the photon,

the tiniest quark of dust

and when God peeped into the void, You were there as the shadow of darkness

omnipresent in the nothingness of things

and when God said let the universe be, You were there as the big that banged, the bang

that bigged

and when God said let us shape the destiny of Man, You were there as the pen and

the scroll, the scribbles and the scribe

A L – A R S H A D poet of many colors

- the purple mare of paradise

- the chlorophyll in the garden of red

- the red arakarabura

- the yellow hissing flames of hell

A L - A R S H A D

the many seasons of songs:

To the Angels

You are the Serpent, the venomous viper filled with bile

To Eve

You are the blessed rod, the pathway to endless bliss,

the monstrous delicious member of Man

To Man

You are vinegar, the white water, crystal drops

the sacred elixir of lust

To Words

You are the emptiness between the letters,

the very gap separating E & O, V & L

to words, You are the neutrinos, the photons, protons of language,

the central atom of speech

To God

YOU ARE THE FORCE

always the FORCE

the pestle that stirred the cosmic soup

when God said LET’S MAKE LIFE

A L – A

R

S

A

H

D - poet of dust

You are A L – A R S H A D poet of dust

the ? that begets question

the lofty permanence absent from the fields

the codex

the invisible secret

the custodians of codes?

al-arshad ? What is the meaning of A L – A R S H A D? :

ALIF: The letter of sand, the invisible

time keeper of the cosmic clock

LAM: The letter of Ram, the sacrificial shards of meat

blood and veins slain at the base of mount arafat,

the clinical tree which extends to heaven to strangulate the jugular of God

AYN: The consonant of light, the eastern duck

that flaps the wings of emerald, the Butterfly,

the Unicorn, the nebula of the horse; the ancient

labor room of stars

RA: dust. The consonant of dust. The brown gazelle gazing

at (mim) the island of frogs & the constellation of Ba

SIN: Sack. The alphabet of the cordage. Strands. Web.

The stellar net, the escape point of earth, Saturn, Pluto & Mars

from the barricading sheets circling the dungeon of God

HA: Heat. The letter of Heat.

Al HamZa :

The letter of light (at the very beginning),

the pointed beak of the paragon of birds,

the bright blackness of the black Madonna, the luminous bulbs

atop the forecastle of the Tall Ships of Sand

Da: t h e D a r k

l e t t e r

Da. The thick black bush of the intercrural valley

Da. The scent. That scent. Cunt. Fuck.

AL – ARSHAD who witnessed the wedding

between sky and God?

Angels? Satan? Black holes? The stars?

Al- ARSHAD - poet of light where can we find the

rare ring of GOD?

is it on his thumb in the arch-horn of Leo

far in the seventy seventh realm?

is it on his magisterial seat in the black hole of miria

where the sacred sound: Om, Om, Om Om is being

continuously fertilized?

is it in the Circular Zone of Flames at the wormhole tak

or is it a string floating in cosmic (un)consciousness or

is it lying flat on al-arsh, the inscrutable throne of God?

AL- ARSHAD did God impregnate the sky to give birth to the universe and dhuljoom?

AL-ARSHAD did the universe impregnate space to give birth to planets and stars?

AL-ARSHAD did the earth impregnate the ocean to give birth to Dinosaurs and Djinns?

AL-ARSHAD did the Dinosaurs impregnate dust to give birth to grass, the green gorilla,

genomes and genes?

AL-ARSHAD how did God impregnate the Sky

if Andromeda is the clean cleavage, and dhuljoom the navel &

milky way the intercrural valley, the garden of the thick black forest,

where the holy apple is grown?

AL-ARSHAD is it the original sin for the phallus to veer through

the intercrural valley, the thick black forest, to seek & taste

the holy apple of life?

*

AL-ARSHAD

how did God mate with Sky

is it with droplets of words, did he say BE and Sky CAME?

and when God said LET THERE BE LIGHT,

and there was light, was that an affectionate smile

from a love struck couple longing for a kiss?

or did God use the Omniscient Force

the ungraspable power of thought?

AL-ARSHAD

To Vandals, inhabitants of Androgassos

You painted the face of God

To Zoks citizens of Kazok, the belt of rocks,

You can perceive the fluorescence of God

To Zelinians of ZHUL

You hold the key to the gallery of truth,

where the invisible portrait of God is kept

AL- ARSHAD

is God the big old man with silver beard smiling in the sky?

is God the Integer, the perfect number of Pythagoras and his ilk?

is God the invisible energy of Socrates & the unmoved mover of Plato?

is God the Lord of the Kaaba, and did he instruct the Bedouins to kill, to cast sacred

stones against his arch enemy iblis?

is God the solar disc of the Aztecs

the Osiris of Egypt &

the total Force of the old African sage?

AL-ARSHAD is God the One, the Oneness of the mystic,

the unity of oneness & the whirling dance of a dervish in a lodge?

A L - A R S H A D

——————————————————————–

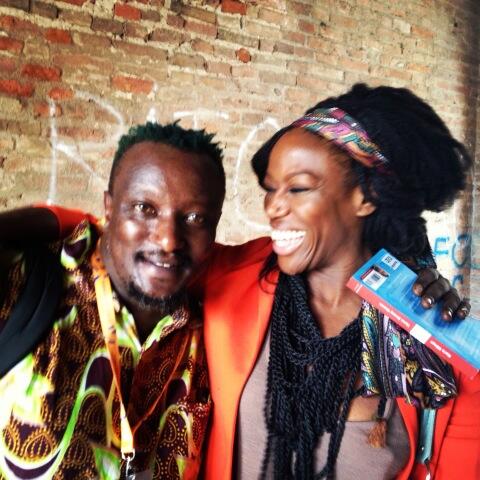

The accompanying images are quite remarkable. They are the work of Algerian artist Sid El Houari, Wahran. You can find his work HERE.

Umar Abubakar Sidi lives in Lagos. “Testament of Sand” is part of a longer work being published by Saraba Magazine. Sidi also has a collection of poem titled “Striking the Strings” that will be released by Origami ( Parresia) sometime this year.