![]()

![Agression - Weate]()

(a story that will surprise you at every turn, a darkish story, a bit of blood to satisfy your hankering for the macabre, but, mostly, a story about love when it shimmers in beautiful and unexpected colors. enjoy reading.)

______________________________

The trouble begins on a hot Thursday afternoon when the sun is boring a manhole in the middle of the earth and my tongue is sticking to the roof of my mouth.

I sit at home, my back to the tin wall, my arms crossed at my chest as the rustling sounds made by the corrugated iron sheets structure tickles my eardrums.

I glare around. Sparse furnishing is distasteful. The biggest article in the shack is the dented mattress on which Dada and I sleep. Its cover is tattered, revealing wrinkled yellow foam here and there. There is a wooden table, a rusty steel chair, and then our clothes, which hang on the wall. Our cooking utensils lay in a pile in the corner. I watch a cockroach climb out of a grimy pot and scurry away, underneath the door and into the sunshine. I need to throw away remnants of food that have gone mouldy. The stench in the shack is bad, as is everything else.

At my tether’s end, I buckle to the temptation to walk down twenty poles to Birnin Afabi where Mai Ajingi sells chilled water and ice blocks from a deep-freezer. When the sun burns as hot as it is right now, Mai Ajingi, the only one who owns a deep-freezer in the shantytown proceeds to wear his bulabula - a big trouser that is wide at the pipes – and day in day out, till charred dust motes rise up and silt the blazing eyes of the raging sun-god, Ajingi fills his cavernous pockets with our hard earned coins.

I step out of the shack and narrow my eyes, my right hand rising instinctively to form a visor. The sun is always too bright and too harsh at this time of the year when harmattan is drawing close. I walk briskly, taking scant notice of anything around me, except a figure hurtling towards me in the distance. He cannot be more than seven years old. He is naked to the waist and he spots a bloated stomach. His attention is riveted on the bicycle tire which wobbles ahead of him while he guides and prods it with a stick. He looks up when it is almost too late and screams a curse, telling me to get out of the way. I flatten against a rusty shack as he blazes past, mimicking a vehicle horn.

I right my cap and snap my fingers. I will find him later.

As I cross the plank-bridge of the Gulengulen drainage, I happen on the crowd.

![Cooling Off With Cold Water by Jeremy]()

Standing in the center of the crowd is the imposing figure of Bareda. He is naked to the waist, and has on a dirty pair of jeans and no shoes. I can see his butt-crack peeping above his waist band. He has a red amulet on his left bicep. There is second man standing in the circle. His is wiry, with bushy hair. His jalabia is dirty, and a long chewing stick wiggles in his mouth as he watches Bareda.

Bareda is stabbing his bare belly with a long sharp blade. The crowd yells and moans and howls in utter bewilderment. Old women grab their prostrate breasts with two hands, whimpering. Younger ones place both hands on their heads.

I forcefully expunge gelatinous saliva onto the dry sands and restrain the urgency of my thirst with both hands. I wipe the sticky remnants of spittle off my dry lips with the back of my hand as I plough a path through the crowd.

“Bring ya hand, you dey fear?” Bareda says, grabbing the right hand of the jalabia-wearing fellow.

The man squirms fearfully, his chewing stick twitching. The crowd bursts into laughter.

“You don rub am? Rub am again…” instructs Bareda releasing his hand.

Jalabia hurriedly dips his hand into one of the white plastic jars arrayed on the ground beside the men and rubs the brownish paste on his hands and neck as directed by Bareda. The crowd murmurs, its voices dissenting. Men urge Jalabia to be a man. Women point out it is not by force. Children cross their hands at their chests and watch with deep interest.

When Jalabia is done applying the ointment, Bareda grabs his right hand and runs the wicked looking blade on the inside part of the elbow, as if to severe arm from bicep. The crowd howls as one, holding their own arms protectively. Jalabia panics too, and attempts to shake free, but he finds himself in a vice-like grip. Then, he realises that there is no cause for alarm. There is no cut, or blood. He relaxes somewhat then, watching the magic, wide eyed.

“Buy odeshi! Na the only odeshi you fit trust be this…” yells Bareda, viciously stabbing the stunned Jalabia in the throat. The blade bounces back with a clinking sound, as if it has struck chinaware. Bareda is prancing up and down, his steps in tandem with a wild tune coming from a radio somewhere.

I scan the crowd for my brother, Dada but I do not see him. This is surprising because it is his kind of gathering.

Out of the corners of my eyes, I see Bareda let go of Jalabia who rejoins the crowd elatedly rubbing his hitherto assailed neck and arms. The crowd welcomes him back like a brother who had been given up for dead – with loud cheers and back rubs and handshakes.

“You, come here,” Bareda suddenly announces, pointing in my direction with the knife.

I look behind me.

“No, you, Ali,” he says.

Ali is my nickname in the shanty town.

Someone in the crowd nudges me forward. I suddenly find myself in the centre, the cynosure of a sea of eyes.

“Rub odeshi on your neck,” instructs Bareda.

I hesitate. The men cheer me on, including Jalabia. The women begin to whimper and wring their hands. One of them calls out my brother’s name when I decide and proceed to rub the nutty smelling ointment on my hand.

“No, on your neck.” Bareda repeats, his eyes hooded.

I hesitate again.

“No, not my neck. My hand,” I say. Some voices go up in murmurs of solidarity, others in catcalls of derision.

I stand my ground. Bareda shakes his head from side to side, his teeth bared in a mirthless grin.

“If I kill you, our people go gree me go?” he asks slashing the air with his knife and drawing an arc across the crowd. The crowd sighs and a portion shrinks backwards in terror.

I smirk, the illogic of his reasoning slaying me. What good is justice to the dead?

“Will vengeance bring me back?” I ask with a smile. There is no laughter in my eyes. His shoulders droop and his face points at the skies. The crowd shifts restlessly. The show has become dull. No crowd likes a dull show.

“Comot, comot,” Bareda waves me away impatiently with the knife, scowling. I leave. I do not fack.

“Anyone with liver? Free odeshi,” he advertises, prancing, slashing and stabbing his own bare body as I return to my position.

The men give me a wide berth. I see relief in the eyes of the women. One old woman prods my head from behind, muttering a rebuke for my acceptance of the challenge in the first instance.

Jalabia is about to make his own submission when suddenly, there is an uproar. I look around. It is Arogu towering to the centre.

Arogu is the head of the Chilo brotherhood. He was born in the shanty and has been in more skirmishes than everyone in our here put together. The scars on his body prove that it is a miracle he is still alive.

He and I had once engaged in a brutal fistfight that had degenerated into a knife fight. I’d broken his jaw and slashed him in the upper arm before he finally responded with a wide handed slash to my face that left an ugly scar running from underneath my left eye and across the bridge of my nose. Folks had then stepped in and separated us.

That was long before the shanty gang rivalries took a deathly turn.

Arogu stands there, in his seven-foot glory, wearing a dirty pair of jeans which had been reduced to knee length with a pair of scissors, and rugged canvas shoes. A toe the size of a baby’s head peeps from his right canvas. He pumps his bare, sweaty barrel chest, and the crowd roars. Bareda stands rooted to the spot, eyeing Arogu cautiously, like a cat. A sixth sense warns me that this sales pitch has taken a quietly dangerous turn. The men’s faces are like those of wild animals, their eyes like serpentine slits in their foreheads.

Both men have retreated into a different world. It is a world infested with a dangerous type of rivalry that festers rapidly like Mai Bagana’s ankle ulcer, a contention that is curable only by slashing blades, mitigating black magic and mindless blood letting.

Arogu pointedly refuses to touch Bareda’s magic paste. He watches as Bareda lifts the knife, and runs it across his own neck, a deathly snarl spreading all over his face. As usual, nothing happens to Bareda. The crowd is silent. The music from the radio takes a cue and stops too. Everywhere is so silent a discerning ear can hear an unruly feather drop.

The crowd shrieks as Bareda charges at Arogu and stations the blade of his karo knife threateningly against the latter’s neck which is wide and thick with dark circular rings, like a drum. Arogu does not flinch. The men glare at each other for a second before Arogu finally faces the skies, presenting his jugular invitingly. My fingers curl, tightening reflexively. How I wish I were the one wielding the Karo.

The crowd holds its breath as Bareda slashes.

It happens, first with the loud bleat of escaping gas. A tentative jet of blood spills forth, some of it landing on my face and lips.

The crowd gasps as Arogu clutches his throat, blood spilling through his black fingers. Arogu crumbles face down like a heap of rubbish, his eyes rolling upwards. Blood gushes out of the open slit in his throat like water from a broken pipe. The slit hisses, expelling air. Bareda crouches defensively and spins around.

We, Shayana are what is left of the crowd.

![Waiting to Fight by Weate]()

It has been two weeks of silence.

Something of an uneasy calm has descended on our shantytown and it clings to us, heavy, like a damp blanket. The afternoon sun blazes still and the smell of our roasting flesh hangs in the atmosphere. The ugly odour of meningitis infiltrates the shantytown and neighbours break out in pus tipped rashes.

The drainage across our back yard suddenly develops the stomach-churning stench of putrefying matter. Dada brings two spades home one evening and hands one over to me. We roll up the pipes of our trousers and stand, our legs spread across the gutter. We begin to scoop out the drainage dregs, dumping them on the ground beside us. Passersby wrinkle their noses and spit as we work. Dada works faster than me, his sinewy arms moving rapidly, a frown on his rugged face.

We work for about twenty minutes before my stomach suddenly heaves and bile rises in my throat. I hold myself as we uncover and hoist the source of the vile stench – a cat. Its belly is swollen and as Dada strikes it with his spade, it rips apart. We can see unborn kitten in a transparent sack, black and white, eaten half and half by termites. I begin to retch.

“Hold yourself,” Dada reels, himself grimacing and turning his head aside to spit for the umpteenth time. A huge Tsetse fly buzzes around my head and I swipe at it, spitting in irritation.

“Brother, this is bad,” I retort, frowning. I am not sure I will ever be able to eat another cat.

“Bad? You don’t know the trouble ahead then. This is child’s play to what will happen,” prophesies my brother, pointing at the greyish horror we have unearthed.

“How did it get here?” I ask, still in shock.

“It is a message,” comes the simple reply from my all-knowing elder brother. We drop our spades and I go in search of a sack.

I return with a brown paper sack with insides still whitish with cement. I hold it open on one end, touching the other end to the ground. Dada, using his spade, carefully rolls the bloated carcass and its spilling entrails into the sack while I hold my nose pinched between my free thumb and forefinger. A mother hen and her chicks squawk excitedly.

Once the carcass is in the bag, I straighten and hoist the package off the ground. I wait to feel the weight hit the bottom before I squeeze the sack, creating a neck. I need no further invitation to begin the long walk to the incinerating well.

“Don’t stay long,” Dada says as he bends his long frame and enters our shack. I do not respond. My belly is running riot. Somehow, I know I will be late.

***

I walk past the rows of shacks that litter the shanty town. I weave in and out of the squatter settlement expertly, taking the short cut to the incinerating well, instead of the longer government main road. I kick a thick white polymer bag ahead of me on the boiling sands, raising dust as I walk. The nylon is stuffed with a piece of red clothing and tied at the end with a string of grass – shanty children’s football.

The shanty town is noisy and replete with gaudy cloth lines this afternoon. The women are clad in Ankara wrappers tied around generous bosoms. They gossip, guffaw, quarrel and call out to their shrieking children. There is the smack smack sound of pounding by wooden mortars and grating noise of mechanized pepper grinding machines.

I stand for a while and watch a woman berate her drunken husband, pounds of meat fretting in her arm as she wags a finger in his face.

“Stupid useless man with small dick!”

She ends the tirade with a vow to find another husband. The grey haired man sits on the bare ground, a puddle of vomit between the inverted V of his spread out legs. His head is bent as if in shame.

He remains in that posture as the woman turns from him and begins to scold a little girl. The child had taken the liberty to relieve herself right at the entrance to her rusty shack.

The shanty gets madder, dirtier and stranger as I walk. It is probably one of the only places in the world where cats and mice roam around in their hundreds and in mutual respect of each other’s space. We humans are reduced feet-stamping on the ground, to scare the indifferent mice away.

After a few minutes’ walk, I see the rail track that leads to the incinerating well. There is the usual litter of boys, sitting on the tracks, surrounded by overflowing garbage. I see little ghetto boys standing knee deep in garbage, poking with sticks, trying to find something worthwhile. The plastic companies reward them well for returning biodegradable materials. Tiregu, Dauda and Asani, Chilo chieftains are seated, as usual in a group. Smaller boys sit around too, here and there. The smell of marijuana hangs thickly in the air as smoke swirls around the boys. I fling my luggage deep into the incinerating well, clap my hands to rid my palms of particles of cement and go to settle on the track, a little away from everyone.

![Railway by Weate]()

I bring out a tiny wrapper of cement paper from my pocket and undo the knot. Dried grass greets my eyes. I spread the wrinkled white sheet of rizler on my palm and empty the weed into it. I discard the empty cement wrapper and seesaw the rizler to achieve an even spread of grass. Then I begin to strap. I strap with expertise.

“Wetin una comot?”

It is Tiregu. I look at him. He’d passed by as Dada and I laboured at the stinking drainage. I’d noticed he had glared at us but no one had said anything.

“Dead cat,” I respond, the symbolism suddenly stinging me. I’d not understood at first.

“Na im be dat?” he asks, pointing at the incinerating well.

“Yes…”

I can see Bareda and Alula and some other Shayana in the distance. Oddly, I do not feel the need for their protection. I’d not become the teenage bare-knuckle champion in the shanty out of luck. It had come out of pure talent, and daily gruelling practice sessions. It is why they call me Ali.

“You heard what happened?” Tiregu asks, not looking at me.

“I was there.” I reply, striking a matchstick.

Warm breeze blows out the light. I strike another, and take care to shield the flame with a cupped palm. It catches on the rizler and I quickly drag and puff until the rizler rustles, coming alight. I blow a thick gust of white smoke upwards, then drop the matchstick carelessly beside me. The flame goes out slowly, in a gentle stream of spiralling smoke till it disperses into thin air.

“It was bad.”

“They were testing medicine,” I defend.

Tiregu falls silent.

There was no gain saying it. Nothing had happened that does not happen all the time. Our shantytown is home to several gangs. The two major gangs are the Shayana and the Chilo. Shayana means “wild cat” while Chilo means “antelope”. Arogu, up till his death two weeks ago had headed the Chilo. Dada and Bareda head us Shayana.

The slaughter incident had lifted a drowsy veil off our eyes. In a shanty, gangs become weak when there is prolonged peace. Gangsters begin to yearn for war, like gun dogs. Rival gangs start to test new medicine in organized contests which invariably breed new violence.

Arogu’s death hadn’t been Bareda’s fault. Someone in the crowd who wanted Arogu dead had probably wielded a medicine more powerful than Arogu’s own. Another possibility is that Arogu’s powers had expired during the months of peace, and he did not know.

Now, the blame of his death lies at the doorsteps of the Shayana. And we are not complaining. Our back is strong.

![Poses by Weate]()

“If anything happens during medicine testing, so be it. It is an unwritten code, a well understood tradition in this shanty,” Dada had said to Bareda after the incident.The interred cat message had come shortly after that discussion, an official statement by the Chilo of the impending reprisal and the form it will take.

Presently, I finger the switchblade tied to my waist underneath my jalabia. The cold metal gives me a feeling of security. I adjust my turban, pulling it closer to my eyebrows so I could covertly observe goings-on in my surroundings. Bareda and Alula get up, and walk towards the road. They ignore the hard glares of the Chilo who are speaking to each other in low tones.

“Ali, let’s go,” Bareda calls out to me from the distance. I wave him away curtly, blowing fumes defiantly upwards in concentric circles.

Maybe I cannot handle three grown up men all by myself, but should these Chilo swine start anything, I am determined to give a good account of myself, for future purposes. Bareda and Alula leave without another word. I see Tiregu place a restraining hand on Asani as the latter starts to rise. I watch all these without appearing to do so. I suddenly feel cold, and alone, and my instinct for survival comes to the fore with full force.

I lurk mentally, like a ferocious cat waiting for the right moment to pounce. I will not wait to be attacked. I ease the blade under my jalabia loose without betraying any movement, readying for a quick draw. I wish now I’d brought Dada’s automatic, for added comfort. I sniff the air, savouring the prospects of a quick kill in this lonesome arena.

Dusk begins to set in and a warm wind fans my face. To relax my nerves, I stretch and arch my back languorously, my hands raised up above my head and clasped at the palms. I hear my spine make a snapping sound, expelling compressed air. The other boys begin to trickle away too, with their loot of biodegradable items. I watch the Chilo from the corners of my eyes. They are still talking in low tones, and I pick an angry bark every now and again.

I smoke the claro off my joint which I hold between the loops of a bent broom stick. I listen to the last seed pop, feel the heat sear my black lips before I drop the joint, and get up dusting the seat of my pants.

“Smally!”

I was expecting it. It is Asani’s voice.

I turn to look at him. He is gangling towards me. His walk is steady on the rail tracks as he holds his arms aloft, like an aircraft’s wings. The distance between us disappears quickly. The others get up too, but they do not move.

“Yes?” I make it a bark.

Asani comes to a halt in front of me, his yellow teeth bared in a vile grin. He jabs me three times on the chest with a finger as thick as a banana. His fingernails are nearer to black than any other colour.

“Tell…tell, tell… Da…Dada that there is no sleep anymore,” he stammers, his head twitching in an uncoordinated manner. I try to avert his foul breath but he is far taller than me. The stench sinks through my headgear and lodges in my nose and throat.

“What did I say?” he asks, pushing me in the chest.

I did not need further invitation.

I swing my fist upwards and catch him in the chin. He reels backwards in surprise, a grunt escaping him. When he opens his mouth, his dentition is a sea of red. He puts a palm to his mouth, stares at it and yelps in horror. I step into him in a flash and another blow explodes on his pointing jaw. I hear bone splinter as Asani shrieks and drops to his knees.

![Swing and Pow by Weate]()

I spin on my heels and make for the main road. Running is difficult on the uneven railroad tracks and I can hear heavy footfalls and rapid breathing behind me.

I sense the duo of Tiregu and Dauda on me before I feel the blow savagely delivered to back of my head. I topple over, my face missing by inches, semi-dry lumps of human waste that clutter the rail track. As I fall, I reach under my jalabia but a crunching kick numbs me. I feel the bone of my forearm give way, a dull ache crawling up my shoulders.

The duo crowd me now, and I look up at their now blurring faces. The retreating sun shines dully behind their heads. They are both yelling at once. I cannot make sense of what it is they say. I only feel heavy blows and kicks fall down on me like rain as the dull dusk lighting slowly diminishes into welcoming folds of utter darkness.

***

I awake to a world that is warm with the aroma of garlic and other spices.

I try to sit up, but I groan and fall back in pain. I lie still on the soft mattress that dips somewhat in the middle, and try to keep my mind blank. Raw pain courses through my head, arms and entire body.

“You are awake.”

The voice is gentle, soft. I let the silky smoothness of it flow through my system, soothing me. I want to turn to look but my head feels like a mortar has been lodged in there. In the topaz glow cast by naked flames, I see a figure bent over cackling fire. Its shadow is divided into two unequal halves on the wall, the top half strangely elongated. The figure moves in a blur, then rises from a low stool, holding a bowl in its hands as it approaches me.

He cannot be more than fifteen years old. He has large roaming eyes and ruddy brown cheeks stained with dirt. His hair is dark and wavy and his jalabia is dirty. He is a Koral, a migrant peasant from Niger. He slowly comes to a stop beside me and sits on the mattress. He reaches somewhere behind me and retrieves a pillow made of tons of intertwined clothing. He leans over me, raising my head up and sliding the pillow underneath. I can smell his body closely. It reeks of dirt, garlic and ginger.

“Is that okay?” he asks me.

The last person who had asked me such a question was mother, ages ago.

“Yes,” I manage.

I swallow thick saliva and my throat explodes. I writhe in pain as I wonder where I am and how I got here, but I cannot muster the strength to ask. The memories of the events of the evening come back to me like a flood. Dada must be worried sick by now. I look out of the open window of the tin shack and see that it is dark outside. I try to think, but my mind is invaded by the krah-krah-krah sounds of the swamp toads, and the chirping sounds of insects.

“Who are you?” I mumble, scarcely hearing my own voice. My throat burns and I fall quiet, exhausted.

“My name is Rasheed,” he says, placing a wet towel on my throbbing forehead.

“Take this,” he says, scooping up a spoonful of hot brown soup.

“It will soothe you.”

I open my mouth and he feeds me, patiently. It is bean soup, salty and spicy. Soon, I start to feel warmth creep into me, and sweat covers me. I find that he has put my right arm in a cast of rags, and rubbed a stinking ointment all over my bruises.

The fever breaks out in the middle of the night. I am covered from head to toe with rashes and goose pimples. I sneeze and retch with an alarming violence that rattles the entire room. The heat radiating from my body spreads all over the bed sheets, burning it up. I shiver and my teeth clatter. The tin walls spin round and round in my eyes. Rasheed swathes me in a bed sheet and rocks me to and fro as I murmur deliriously.

I watch the candle flare as if from another realm. It puts up a good fight to stay alive as a dusty gale begins to blow, rustling the leaves outside and rattling the tin shack. The flame dies eventually as I drift into an uneasy calm.

I awake to harsh sunshine and singeing heat in the afternoon. I feel too weak to open my eyes. I listen to Rasheed as he moves about the shack, whistling. I force an eye open and blink at the cruel lighting. A tremor runs through my head and I keep my mind blank to ease off the pain. Rasheed is standing over at the door, blowing off chaff from roasted groundnuts. He finally turns and comes back inside and his eyes and mine meet.

“Who beat you up that way?” he asks, standing over me, tossing the nuts into his mouth.

“Some boys,” I answer. “It was my fault. I hit one of them first.” I quickly add. My throat feels like a desert – parched.

“Chilo?”

I nod.

“Are you Shayana?”

I nod again. The flame red cat tattoo on my right bicep said it all.

“They have burned down Birnin Fada,” he informs me.

“Chilo and Shayana?” I breathe.

It is his turn to nod.

I close my eye and lay still.

Rasheed explains that he had been in the mammy market in the morning when it started. He learned that there was an ongoing search for a teenager who had gone out and not returned home last night.The Shayana had come to the rail tracks to look for me but it seemed I’d disappeared into thin air. Enraged and convinced I’d been murdered by the Chilo, the Shayana had struck.

“You have to stay here for a while, till things cool off,” Rasheed finishes.

“I have to get word to my brother, Dada. You know him?” I croak.

Rasheed nods.

“Tell him where I am.”

“Okay, but you must eat first.”

He feeds me again, with the left over bean soup.

It tastes even better today and he stares into my eyes as he feeds me, an almost motherly look creeping into his watery eyes.

He helps me hobble to a nearby bush and leaves as I crouch in the shrubbery. Huge flies with greenish bottoms buzz around me as my bowels rumble. I let out fleeting gas and pass a rushing, endless stream that leaves a peppery sensation in my anus. My belly is soon empty and I am too weak to stay balanced on the balls of my feet.

Rasheed calls out to me from the distance, saying that he is going in search of Dada. I say thank you, hoarsely. I am not sure he hears me, but he leaves all the same. I wipe my buttocks with leaves, and hobble back into the lonely shack that overlooks the rail tracks, and lay on the mattress.

The room is almost empty, except for a few clothes hanging on nails. His kitchen is in full glare. Odd assortments of food items lay on the floor, some tipping out of nylon bags. Cockroaches and lizards dart in and out of hidden crevices. I drag my eyes off the squalor and slowly drift off into a disturbed slumber.

I dream of being surrounded by machete wielding Chilo, all of us trapped in a burning shanty house.

***

Dada did not come back with Rasheed in the afternoon, but he sent word that he would come as soon as it was dark. He arrives as twilight appears in the horizon and he hugs me a little too tightly.

“You are truly a cat,” he says.

I nod, joyful for my brother’s commendation. It does not come often. Rasheed has a sad, almost remorseful look in his eyes as we leave and I did not turn back to look at him.

Dada and his friends ferry me home on a stretcher under the sombre watch of moonlight.

As our little party travels, the men regale themselves with tales of the clash, how Shayana blades had slashed and flashed, traced fine arcs in nothingness, and wrought horror on the flesh and bones of howling Chilo.

![Taiye by Weate]()

I imagine the music of it all, bone splintering under the brazen ministration of steel, lacerating flesh, turning up white fat, before red liquid sprays forth. I salivate. Shayana are buoyed by blood chilling screaming. But the district is silent now; a guttural silence that one cannot get used to or forget. The silence reeks of an eerie suddenness and hollowness, like that unexplainable spectre, in which everyone in a chatter-filled shack suddenly fall quiet, for no obvious reason.

We speed quietly through the district that now seems unbalanced, sitting precariously in a perpetual slant, like a saucer on a precipice. We cross myriads of traders’ stalls that lay in ruins. There are series of black mounds in the middle of the roads, metal threading from burnt tires in intricate tangles with each other. The stench of burned flesh sits deep in the atmosphere. It will be like that for a long time.

Someone shows me a severed human hand on the ground. It is long and wiry with crooked, gnarled fingers. It is the kind of hand created to wield axes, the kind of hand that could only have belonged to a Chilo.

“Chimpolo’s” Dada simply says. Chimpolo was a Chilo who got his nickname from his looks.

The Chilo had suffered alarming casualties. Tiregu’s head was almost hacked off his neck with a sickle. Some were shot, several were hacked to death in their shacks and others tied together and burned like refuse.

Such is the face of shanty anger and vengeance when the mask of peace is doffed.

***

It is late in the night.

I hobble on, a lonely figure under the demure moonlight. Ever since the skirmish, I only come out at night, wrapping the cloak of darkness smugly around me. I do not meet anyone as I exit our shanty town. Everyone is safely locked indoors, and I am grateful for that.

I soon reach my destination, and rap gently on the door of Rasheed’s shack. He is seated on his low stool making bean soup. He does not say a word as I limp inside and go on to sit on the mattress. I have not seen or heard from him in the past two weeks. I gently lay my crutch stick on the floor beside me.

The room has the same dull glow from the flame in the lantern. The aroma of the bean soup makes my belly growl. I have not eaten all day.

“You are better now?” he asks when he senses I have settled in well enough. His inflection quickens the blood in my system. He still has not turned to look at me. His back looks broader than I remember it.

“Yes, thank you,” I reply, stretching out on the bed.

A hot breeze blows and I watch the leaves on the Gmelina tree outside sway. A pig grunts in the nearby garbage.

“There is a lot of rebuilding going on at the shanty.” I say. I want to hear him talk.

“The ruin is great,” he replies.

I sit up slowly.

“Can I stay here till all is done and ready? Hope you don’t mind?” I finally blurt out what has been on my mind.

Rasheed does not respond. He just continues with his cooking. If he wonders how much of a pest I am, he does not say so. He just cooks in silence. As I watch his delicate almost womanly movements, I realize I will need his care. I know who he is. And I know he knows who I am. The eyes do not lie.

Finally, he gets up from the low stool, bean soup bowl in his hands, and walks slowly towards the mattress. He sits beside me and sets the steaming bowl on the ground. I lean back into the mattress and close my eyes. Rasheed’s soft lips crush mine with a feverish urgency. We go at each other for a long time, straining and panting heavily like wild dogs on searing heat, the spicy aroma of bean soup warming the air.

When one finds home, the heart is at rest.

Many thanks to Jeremy Weate for the permission to use his beautiful photographs of the Dambe fight—a Hausa boxing ceremony—and of the railroad.

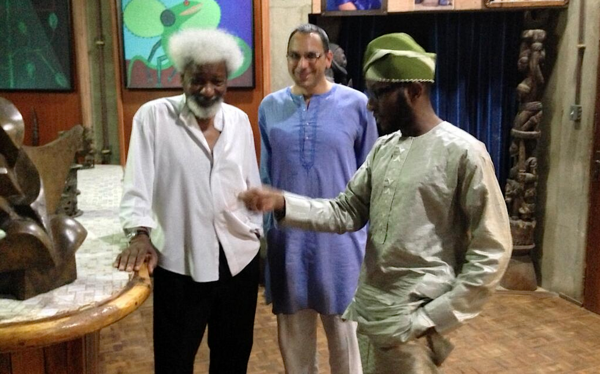

![Niyi Omojola - Portrait]() Oluwafunminiyi Omojola is a Nigerian writer who is also a banker. Being a Yoruba man who is married to a Hausa lady and resident in Iboland, Funminiyi considers himself an epitome of the detribalised Nigerian.

Oluwafunminiyi Omojola is a Nigerian writer who is also a banker. Being a Yoruba man who is married to a Hausa lady and resident in Iboland, Funminiyi considers himself an epitome of the detribalised Nigerian.

His poems and short stories have appeared in many news dailies and magazines around Africa including The Sunday Sun, This Day, and The Kalahari Review.

Kachi held the door knob tightly as it turned inside her fist, hoping to seize its sounds in the spaces of her fingers. It didn’t work—the door snapped and clicked and groaned as she tried to push it open gently. She cursed under her breath, using those sharp dirty words her mother would slap her for. The traitor door creaked happily as she tried to close it behind her, the soft of their welcome mat eating up the heel of her shoes. She balanced and bent to slip the first shoe off so she could tip toe over the dark hardwood and sneak into the bathroom. Maybe he would hear the water and just think she’d woken up to pee or something. Pressing her palm against the door, she wobbled as she lifted up a foot, the wine from earlier still winding through her.

Kachi held the door knob tightly as it turned inside her fist, hoping to seize its sounds in the spaces of her fingers. It didn’t work—the door snapped and clicked and groaned as she tried to push it open gently. She cursed under her breath, using those sharp dirty words her mother would slap her for. The traitor door creaked happily as she tried to close it behind her, the soft of their welcome mat eating up the heel of her shoes. She balanced and bent to slip the first shoe off so she could tip toe over the dark hardwood and sneak into the bathroom. Maybe he would hear the water and just think she’d woken up to pee or something. Pressing her palm against the door, she wobbled as she lifted up a foot, the wine from earlier still winding through her.